Every child has the right to live in safe, secure, healthy and sustainable environment. This right is enshrined in the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child and, explicitly or implicitly, in the Constitutions of most, if not all, countries. It is evident that each time the environment is harmed or destroyed, the rights of children are violated, or are effectively denied them. Without a safe and sustainable environment, it is difficult to imagine how the children can enjoy their basic rights to survival, protection, participation and development. Any harm done to the environment impacts on the rights of children at the present moment and in the future.

Let me cite one example to be concrete. Many of our forest covers in the Philippines are gone. Samar Island, for instance, in 1952 had 86% forest cover. In 1987, thirty-five years later, Samar had only 10% forest cover remaining. And for all its rich natural resources, most of the people in Samar remain very poor. In recent years, the people of Samar have been hit by deadly flashfloods, and many kinds of natural disasters which crossed the island like the super-typhoon, Haiyan/Yolanda in 2013 which ravaged Guiuan and other coastal parts of Samar. And sadly, this case is not isolated. One can see this denudation of forests in many other islands of the Philippines and in many parts of Southeast Asia. The adverse impact of forest denudation to children is obvious and indisputable both in the short- and long-terms: instantaneous deaths of children who are most vulnerable to disasters, homelessness, food insecurity and loss of biodiversity which leads to malnutrition and starvation, impoverishment of families who as a consequence cannot send their children to school, cannot provide decent homes and the opportunities children need to grow.

Moreover, the link of development to child rights and environment is very clear. The model of social development a government adopts, in many ways, affects environment and human/child rights. For instance, the neo-liberal development model, dominant in many Southeast Asian countries, applies the policies of privatization, deregulation and liberalization. The over-riding aim is to realise economic growth and profit maximization. As a result, health and education services are privatized; and when they become profit-oriented, they are unaffordable to many children, and thus becoming a privilege to a few rather than a basic right to all children. With low budgets allocated by governments to health and education, what is accessible are services of very poor quality.

Terre des hommes’ strategic goal on Ecological Child Rights points out, (and I make full quotes of the contextual analysis and orientation of the strategic goal defined by the Delegates’ Conference):

…the necessity of an intact natural environment for the welfare of children. Children and youth have the right to an environment in which they can grow up healthy and which – sustained by cultural and biological diversity – enables them to comprehensive developmental opportunities and positive future prospects. That presupposes the preserving of natural resources, forms of cultural, social and economic life adapted to local living conditions, successful adaptation strategies to environmental changes. What should be taken for granted is being called into question by the depredation of natural resources and the progressive environmental and the climate crisis. Children and young people are particularly affected by these developments.

The unbridled exploitation of natural resources impairs the livelihoods and scope for action of many people; the loss of cultural and biological diversity reduces adaptation options and thereby survival chances. These conditions lead to natural and human-induced disasters which claim for more and more victims, particularly among poor population groups who are driven off into risk areas.

Environmental awareness and biodiversity are closely linked to traditional knowledge of local cultures and their understanding of nature. The privatisation of community land and commercialisation of commons such as knowledge, seed, forests or water reduces self-sufficiency in meeting basic needs, and thereby the future prospects of all.

What is needed is more political pressure from below and real-life alternatives, ensuring land rights and land use of poor and marginalised communities. A public and political recognition of the rights of children and youth to an intact environment must be reflected in laws and the changed behaviour of governments, corporations and each individual person. Children and youth are themselves agents of change, and can act to protect and strengthen an intact natural environment. This forms an essential element for enabling sustainable development and intergenerational justice in general (Strategic Goal on Ecological Child Rights as approved by the Delegates Conference 2013, p.7).

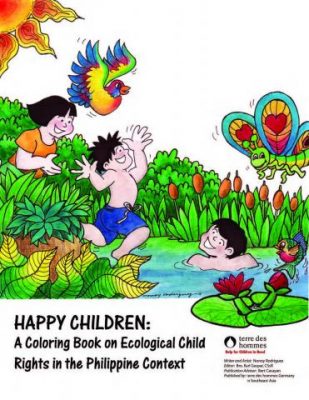

This book on Ecology and Child Rights in the Philippine context – a result of three decades of work in environmental issues in Mindanao – shows the link between environment and child rights. The presentation heightens our awareness to the strong interlinks between nature and humans, and the critical conditions of the environment in our times. Unless, we join together and act now to arrest the degradation and destruction of the environment, we will all suffer and rob our children of a healthy environment which adults owe them. In fact, unless all actors—governments, private sector, civil society organisations and other sectors, act effectively, we may all perish!

It is our fervent hope that this small initiative will make a contribution to this awareness. A drop in a vast ocean it is, but hopefully it is a sparkling drop which can inspire many.

Alberto Cacayan

Regional Coordinator

Bangkok, 30 May 2015

Download the Coloring book on Ecological Child Rights in the Philippine Context, here.

Download the Handbook for the teachers and parents for the ECR Coloring book, here.